Blocking and non-blocking I/O

Reading time: 5 minIf you haven't read the blog post about concurrency and parallelism, I highly encourage you to do so before reading this one.

When people hear “I/O,” they usually picture the following:

- app needs to perform read/write operations on a file

- app needs to execute some query on the database

- app needs to execute some HTTP network request towards some REST/SOAP/... client

Those 3 are indeed the most common types of I/O. Are there any more?

- You're playing video games? GPU calls are I/O

- Message queues (Kafka, RabbitMQ...)

- random devices (

/dev/urandom)

Simply put, as soon as the application needs something completely outside its memory space, it's doing I/O.

There are 2 types of I/O: blocking and non-blocking.

Blocking I/O #

The simplest form of I/O. It executes as following:

- Your application-executing thread asks to interact with a piece of data outside its memory space via syscall (such as

readorwrite), providing it a location in memory - If the data is immediately there in memory, the kernel returns the data to the calling thread

- If not, the kernel sends the request downstream, to the physical I/O device's driver (disk, NIC, GPU...)

- Since the kernel knows the data is going to take some time to arrive, it will suspend the calling thread (put it to sleep). Suspended thread is unable to do anything else, until the data comes back

- A blocked thread consumes zero CPU. It is parked until interrupt occurs (more details in step #6). It only takes some amount of RAM

- Once the data is received by the physical device, it feeds it to the RAM (typically into a socket kernel buffer) thanks to DMA

- Once the data is fed into the RAM/into the location specified by the calling thread at step #1, the physical device triggers an interrupt

- Thread is marked as un-suspended by the kernel (the result of an interrupt) and when it gets it's chance for execution, it will have the data in it's memory

Blocking I/O Code Example #

Here's a quick little example of blocking I/O, using server in C and 2 clients connected to it via netcat. Open 3 tabs/windows in terminal of choice. In the first tab, create blocking.c file with the following content:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#define PORT 9000

#define BACKLOG 2

#define BUF_SIZE 1024

int main() {

int server_fd, client1_fd, client2_fd;

struct sockaddr_in addr;

socklen_t addrlen = sizeof(addr);

char buf[BUF_SIZE];

server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (server_fd < 0) { perror("socket"); exit(1); }

addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

addr.sin_port = htons(PORT);

if (bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, sizeof(addr)) < 0) { perror("bind"); exit(1); }

if (listen(server_fd, BACKLOG) < 0) { perror("listen"); exit(1); }

printf("Blocking server listening on port %d\n", PORT);

printf("Waiting for first client...\n");

client1_fd = accept(server_fd, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, &addrlen);

printf("Client 1 connected, fd=%d\n", client1_fd);

printf("Waiting for second client...\n");

client2_fd = accept(server_fd, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, &addrlen);

printf("Client 2 connected, fd=%d\n", client2_fd);

while (1) {

ssize_t n;

// Blocking read from client1

n = read(client1_fd, buf, BUF_SIZE-1);

if (n > 0) { buf[n] = 0; printf("Read from client1: %s\n", buf); }

// Blocking read from client2

n = read(client2_fd, buf, BUF_SIZE-1);

if (n > 0) { buf[n] = 0; printf("Read from client2: %s\n", buf); }

}

close(client1_fd);

close(client2_fd);

close(server_fd);

}Compile and run it: gcc -o blocking blocking.c && ./blocking. The server is now running in the first terminal tab.

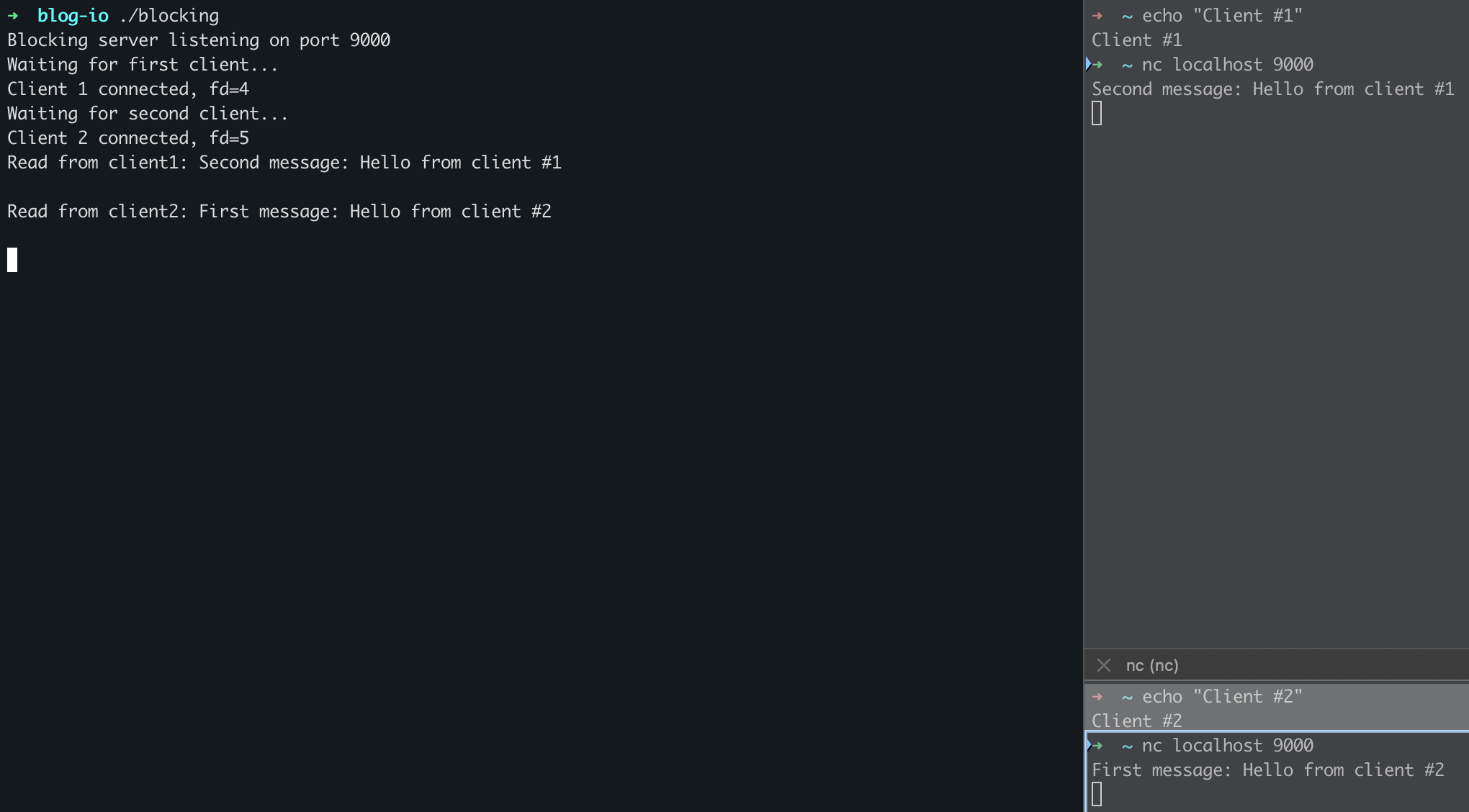

Let's connect two clients via netcat in the two remaining terminal tabs. Run the same command in both of them: nc localhost 9000. Let's send some data.

Enter First message: Hello from Terminal #2 in the second client terminal. Check the server's output. Nothing... That's because the server is stuck waiting for the first client to send data. Important thing here to keep in mind is that, even though server doesn't know that 2nd client has sent the data, it's buffered in memory, so as soon as server is done reading first client's data, it will immediately read the data sent from the 2nd client.

Now go to the first client's terminal and enter Second message: Hello from Terminal #1. Check the server's output. We can see now that both "Hello world"'s have been printed, with second message (sent from the first client) being first.

Non-blocking I/O #

Here's what's going on when non-blocking I/O is utilized and how it differs from blocking I/O:

- Your application-executing thread asks to interact with a piece of data outside its memory space via a syscall (such as

readorwrite), providing a location in memory- The file descriptor is explicitly marked as non-blocking in this case

- The kernel checks whether the requested operation can be completed immediately using data already available in kernel memory (socket buffer, page cache, etc.)

- If the data is immediately available, the kernel copies it into the user-provided memory and returns to the calling thread

- If the data is not available:

- the kernel does not suspend the thread

- the syscall returns immediately with an error indicating “would block” (e.g.

EAGAIN/EWOULDBLOCK)

- The kernel still sends or keeps the request downstream to the physical I/O device’s driver (disk, NIC, …) so the data transfer can happen asynchronously

- When the physical device receives the data, it feeds it into RAM (typically into a socket kernel buffer) using DMA

- The physical device triggers an interrupt, informing the kernel that new data is available

- The kernel marks the associated file descriptor as ready (readable or writable)

- It is now the application’s responsibility to:

- try the syscall again, or

- be notified via a readiness mechanism (

select,poll,epoll,kqueue, etc.)

- When the application retries the syscall after readiness, the kernel copies the now-available data into user memory and returns successfully

Non-blocking I/O Code Example #

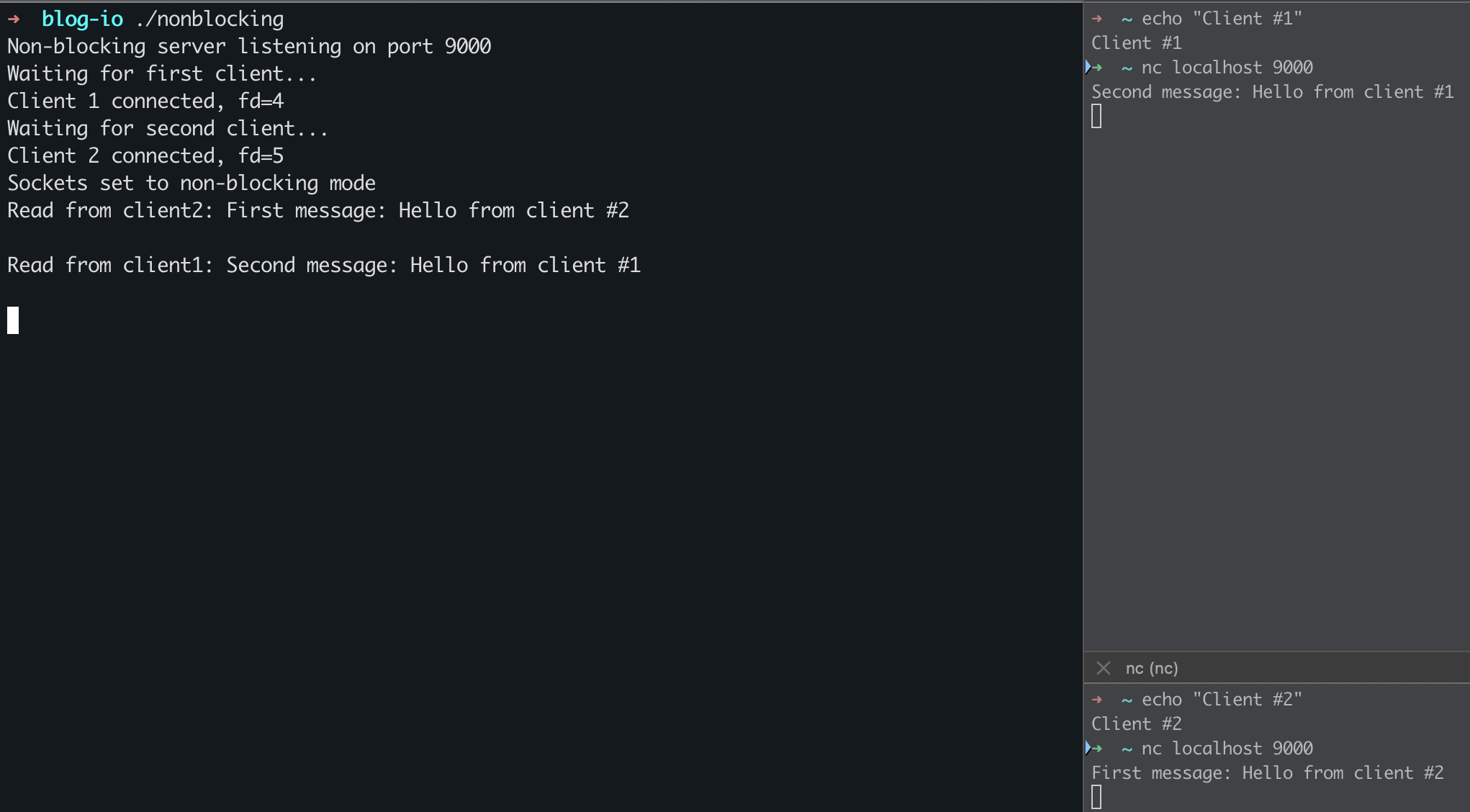

Same configuration, one server and 2 clients, this time the file name is nonblocking.c and the command is gcc -o nonblocking nonblocking.c && ./nonblocking.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#define PORT 9000

#define BACKLOG 2

#define BUF_SIZE 1024

// explicitly mark file descriptor (fd) as non-blocking

void set_nonblocking(int fd) {

int flags = fcntl(fd, F_GETFL, 0);

fcntl(fd, F_SETFL, flags | O_NONBLOCK);

}

int main() {

int server_fd, client1_fd, client2_fd;

struct sockaddr_in addr;

socklen_t addrlen = sizeof(addr);

char buf[BUF_SIZE];

server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (server_fd < 0) { perror("socket"); exit(1); }

addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

addr.sin_port = htons(PORT);

if (bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, sizeof(addr)) < 0) { perror("bind"); exit(1); }

if (listen(server_fd, BACKLOG) < 0) { perror("listen"); exit(1); }

printf("Non-blocking server listening on port %d\n", PORT);

printf("Waiting for first client...\n");

client1_fd = accept(server_fd, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, &addrlen);

printf("Client 1 connected, fd=%d\n", client1_fd);

printf("Waiting for second client...\n");

client2_fd = accept(server_fd, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, &addrlen);

printf("Client 2 connected, fd=%d\n", client2_fd);

set_nonblocking(client1_fd);

set_nonblocking(client2_fd);

printf("Sockets set to non-blocking mode\n");

while (1) {

ssize_t n;

// this time, both calls to read syscall will not block, but immediately return, per step #4 above

n = read(client1_fd, buf, BUF_SIZE-1);

if (n > 0) { buf[n] = 0; printf("Read from client1: %s\n", buf); }

n = read(client2_fd, buf, BUF_SIZE-1);

if (n > 0) { buf[n] = 0; printf("Read from client2: %s\n", buf); }

usleep(100000); // small sleep to reduce CPU usage

}

close(client1_fd);

close(client2_fd);

close(server_fd);

}

You can clearly see that in non-blocking case, first message sent by the second client is properly printed first on the server. But in the case of blocking I/O, the server waited for the first client to send the message, even when the second client sent the message first.

To be fair, I kind of deceived you. There is a 3rd type of I/O: Async I/O. The difference between non-blocking and async can be simplified like so:

- Non-blocking I/O asks: “can I do this now?”

- Asynchronous I/O says: “do this, and tell me when you’re done.”

But that topic is for another day.